Blog

Challenging assumptions: why girls with disabilities return to school

Since 2012, the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) has been supporting the most marginalised girls through quality education and learning. Most GEC projects actively seek to include girls with disabilities in their work. Over the years, the GEC has also contributed to the wider discussion on how to identify and support the most marginalised girls in education, including girls with visible and invisible disabilities[1] in and out of school. Evaluations have shown that up to 16% of GEC girls have disabilities, with many facing psychosocial difficulties including anxiety and depression.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, children with disabilities faced significant multiple vulnerabilities, including education, health, and social protection, as highlighted by the recent World Bank's Inclusive Education Initiative (IEI) report [2]. The GEC found that marginalised girls were particularly at risk of disengaging from learning due to financial hardship, food insecurity, caregiving responsibilities, sexual and gender-based violence and early marriage or pregnancy. We anticipated that girls with disabilities would struggle to go back to school, given these challenges.

However, an initial look at re-enrolment in schools in 16 projects across Africa and Asia showed a different story. At least 11 projects had return rates of girls with disabilities into school at the same rate or higher than overall attendance patterns. This high rate of return of girls with disabilities challenged our assumptions, given that they often face more educational barriers than their peers.

Why were these rates so much higher than expected?

Girls’ voices were sought, listened to and used to inform programming. Projects sought to understand the experiences, challenges and needs of girls with disabilities during school closures and saw how the interplay of social characteristics can increase vulnerability and inequality. This reinforced that girls with disabilities are not a homogenous group, and how treating them as if they are all the same undervalues their differences, including how they experience disability as well as being female.

Each project conducted a Gender and Social Inclusion (GESI) Analysis. This recognised that girls, including those with disabilities, do not exist in isolation. Factors including where they live, their family set up and levels of poverty all combine to intensify barriers to education. However, with girls with disabilities, the barriers are often assumed to be the girls’ own challenges due to their impairments, rather than a result of the interplay between social norms, stigma, and inadequacies of the education systems. The contextualised analysis conducted by projects expanded their understanding of how to address these complex barriers.

Community-based systems were used to safely keep in contact with girls and keep them engaged in learning. During COVID-19, retention systems which tracked and supported girls to stay in school became less formal and more community based. These included various local education committees, women’s groups and organisations of persons with disabilities. These groups were well placed to respond to the multiple challenges girls with disabilities faced as they were trusted by communities, already were part of monitoring processes and provided feedback loops, and worked with local structures, including safeguarding referral systems. These networks utilised previously held data and adapted remote data collection and analysis to directly support girls at risk of dropping out. They worked best when they represented diverse groups and were linked to actors and systems including health, protection and social services. Once schools reopened, these networks also supported girls’ reintegration to school.

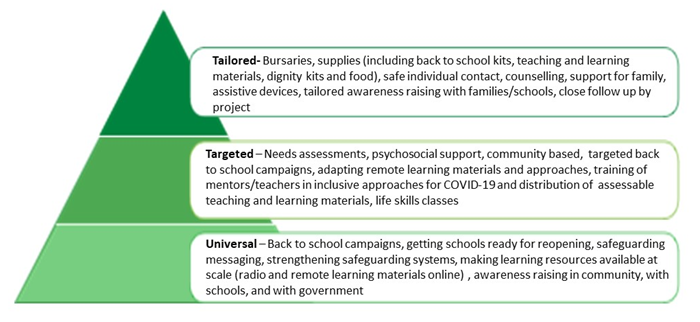

Intervention design took a three-pronged approach. During COVID-19, projects pivoted quickly to keeping in touch with the girls in a safe way that reduced isolation and girls learning. Successful interventions focused on three levels: universally working with schools and communities; targeting groups of at-risk girls; and tailoring interventions for individuals. Community-based systems created enabling environments for girls to continue learning through GESI analysis and strategies, challenging gender and social norms and attitudes towards violence, and championing all girls’ right to education. This complemented more practical solutions including psychosocial support, targeted assistance and accessible learning materials. Closely tracking attendance was also important. Essential services and therapies were closed during this time, and GEC projects supported girls with disabilities to make sure their basic needs were met.

For example, Plan International’s Girls’ Access to Education-Girls’ Education Challenge project in Sierra Leone (GATE-GEC)[3] had 99% of girls with disabilities return to school after school closures. They did this through the following interventions:

While the GEC, like other programmes, is working with limited evidence regarding COVID-19 and its impact on girls with disabilities, the focus on safety, gender and social inclusion underpinned all other COVID-19 work and showed some early, positive results.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

[1] Understanding and Addressing Educational Marginalisation, 2018, Girls’ Education Challenge, available at https://girlseducationchallenge.org/media/racfdc1i/thematic-review-addressing-educational-marginalisation-part-2.pdf

[2] Pivoting to Inclusion: Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis for Learners with Disabilities, 2020, World Bank’s Inclusive Education Initiative (IEI), available at Pivoting to Inclusion: Leveraging Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis for Learners with Disabilities (worldbank.org)

[3] GATE-GEC is led by Plan International UK and implemented by Plan International Sierra Leone and partners Action Aid, Humanity and Inclusion, and the Open University. More information is available at: https://girlseducationchallenge.org/projects/project/girls-access-to-education/#/article/girls-access-to-education