Blog

Education programming in a pandemic: Using what we already know about girls to support them during and after Covid-19 school closures

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in more than a billion children in 191 countries unable to physically access schools due to closures (1). Previous experience tells us that local, national and global crises negatively affect education systems and children’s learning - disproportionately affecting learners who are already marginalised, including girls (2). Evidence from previous school closures (for example, during the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone) also shows that girls are at greater risk of permanent drop out once schools open (3).

During the last year of school closures, there has been much talk about appropriate ways to change programmes to mitigate these risks. However, programme designers and implementers have not always been sure how to interpret evidence from pre-Covid-19 times in the time of Covid-19 itself.

The GEC is the largest donor-funded girls’ education programme in the world and has provided a unique opportunity to look at previous evidence from the programme and think through the implications of this evidence for girls’ education, during and following school closures. This blog outlines some recommendations for programmes to ensure girls’ learning, based on emerging learnings from the GEC.

In 2019, Oxford Policy Management and Oxford MeasurEd were commissioned by FCDO to combine and analyse datasets from the 27 independent GEC-T project-level evaluations, in order to contribute to the evidence-base on girls’ marginalisation and the barriers they face in attending school, performing well and transitioning into secondary school or vocational training.

The database provided useful information on the characteristics of girls, their experiences of schooling and their baseline learning levels.

In April 2021, the research team from OPM and Oxford MeasurEd worked together with the GEC Fund Manager to review (1) what we know about marginalised girls based on the findings from the baseline analysis, and (2) what we know about their learning and how these characteristics are associated with learning. We then identified what this might mean for programmes working with marginalised girls during the pandemic.

The team included Rachel Outhred, Maria Ogando Portel, Katherina Keck and Alasdair Mackintosh.

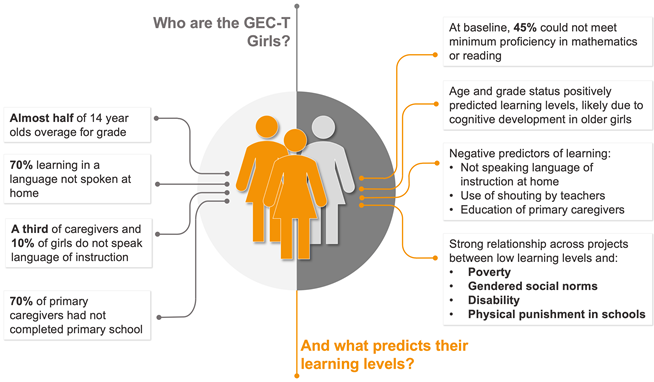

Who are the GEC-T girls?

Below we present a few key characteristics of the GEC-T girls at baseline. However, the full report provide much more detail. The full report is available here.

GEC-T projects support over 1.3 million girls across Africa and Asia, with approximately half of the girls in Eastern and Central Africa.

Our analysis found that the average age of a girl supported by these projects is 14, but overall the girls range from six to 23 years of age. Being overage for a grade is very common, with almost half of 14 year olds being overage.

Almost 70 per cent of GEC-T supported girls are learning in a language that is not the main language they speak at home and a third of the girls’ primary caregivers do not speak the language of instruction. Over 10 per cent of girls are learning in a language that they do not speak at all.

Over half of the GEC-T supported girls are from households that experience difficulty sending girls to school and over 70 per cent of the primary caregivers of GEC-T girls had not completed primary school.

What were the girls’ baseline learning levels and what individual and school characteristics predict learning?

The full report is available here.

Our analysis found that at baseline (prior to participating in GEC-T), approximately 45 per cent of the girls could not achieve a minimum level of proficiency in mathematics or reading.

In order to understand the relationship between the girls’ maths and reading proficiencies and what we know about the girls, their homes and their classrooms, we analysed the predictors of learning (4).

Our global analysis found that not speaking the language of instruction at home, the teacher using shouting as a form of discipline and the primary caregiver having no education negatively predicts meeting a minimum mathematics proficiency level. Girls reporting that chores interrupt their schooling strongly negatively predicts learning for reading. Our analysis across the 27 projects found an important relationship between lower learning levels and poverty (the role of the primary caregiver and economic barriers), gendered social norms (the domestic burden on girls), disability, and the use of physical punishment in schools. These relationships remained important across the projects.

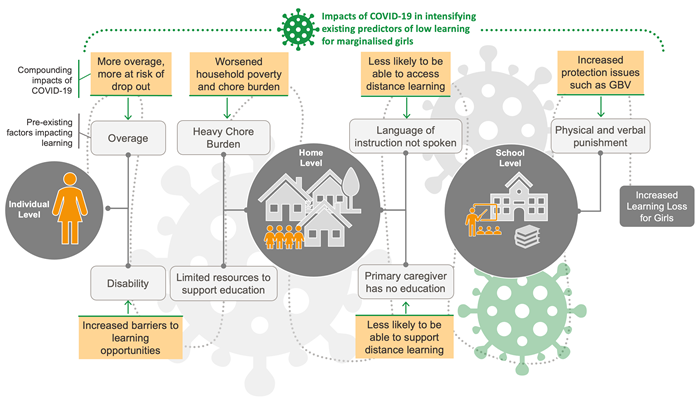

Implications for the impact of Covid-19 on marginalised girls

Anita Reilly, Teaching and Learning Specialist with the GEC Fund Manager, used the analysis to reflect on the impact Covid-19 is having on the predictors of learning. In the diagram below, the orange boxes illustrate the predictors of low learning identified in the baseline analysis. The grey boxes illustrate the further negative impact of Covid-19 on learning at the individual, community and school levels, based on emerging learning from the GEC.

The individual level. Because many girls have missed a year of schooling, they are more likely to be overage when schools re-open. The older a girl is for her grade, the more at risk she is of permanent drop-out. Many girls with disabilities were disproportionately affected as schools closed as they faced increased barriers to accessing learning opportunities. Several GEC projects are already reporting a widening of the learning gap between learners with disabilities and their peers.

The household level. Covid-19 has worsened household poverty levels which is negatively impacting girls’ learning, both through the increase in household chore burden, as well as through the lack of resources to support distance learning. Caregivers who don’t have a formal education have reduced ability to support girls’ distance learning as compared to better educated caregivers. Also, home learning may be more difficult for girls in households where the language of instruction is not spoken.

The school level. The use of verbal and physical punishment was found to negatively predict learning for GEC-T girls. While the use of physical punishment in schools may not be a risk during school closures, worryingly, GEC projects have reported increases in violence and early pregnancy during the pandemic – in addition to increases in girls’ anxiety and stress levels. As schools re-open, it’s more important than ever that learning environments are safe, nurturing and healing.

Considerations to support the learning of marginalised girls

The following are considerations for practitioners and policymakers based on the baseline analysis and emerging learning from the GEC.

- Implement inclusive (re-) enrolment and retention strategies, focusing on ensuring strategies are reaching the most marginalised girls.

- Offer alternative pathways such as accelerated education, catch-up or non-formal programmes for overaged girls who no longer consider formal education as a viable pathway.

- Ensure that distance learning opportunities are accessible to all learners, particularly learners with disabilities.

- Provide distance learning through home learning and/or small group learning for the most disadvantaged to ensure learning gaps are not widened.

- Assess the learning levels of girls when they return to school, to inform the development of support strategies (remedial, catch up or other programmes) to narrow learning gaps.

- Actively work with parents and caregivers to ensure they are supporting girls’ home learning.

- Prioritise the safety and wellbeing, both at home and in school. This should be a priority for all girls but with a particular focus on the most vulnerable.

As 11 million girls globally are at risk of not continuing their learning due to Covid-19, to avoid widening the gender gap in education, it is more important than ever to identify girls most at risk of not learning and to ensure they are reached and supported.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(1) UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/news/13-billion-learners-are-still-affected-school-university-closures-educational-institutions

(2) Bandiera, O., Buehren, N., Goldstein, M., Rasul, I. and Smurra, A. (2020) Do School Closures During an Epidemic have Persistant Effects? Evidence from Sierra Leone in Time of Ebola Cambridge, MA: J-PAL.

(3) Berry, C. and Davis, E. (2020) ‘Mitigating COVID-19 Impacts and Getting Education Systems Up and Running Again: Lessons from Sierra Leone’ 22 April. UKFIET: The Education and Development Forum.

(4) In statistics, a predictor is a variable that can be used to predict the value of another variable. In this case, that other value is learning. The predictor could be a feature of the individual learner, of what happens in their school, or of characteristics of their home and predictors can be negative or positive. Negative predictors are characteristics or behaviours that are associated with lower learning levels. Positive predictors are characteristics or behaviours associated with higher learning levels.