Blog

Inclusive education or exclusive education?

More specifically, are we promoting inclusive education in a way that truly benefits all children?

The purpose of this blog is to encourage constructive discussion among stakeholders. To create inclusive, equitable and sustainable education systems, we need to ensure that children with special needs are not excluded.

Initial data from research conducted by World Education in Ghana indicates that in all the efforts to create inclusive regular schools for all, we might overlook a group of children most in need of our support.

We are referring to children with severe disabilities currently in Special Needs Education. The desire for a fully inclusive system is laudable, and many are working towards progressive universalism. However, the reality is that in many countries, Ghana included, Special Needs Institutions, play an important role in delivering education for children with severe and profound disabilities. Despite this, Special Needs Institutions tend to operate outside of mainstream education and are not part of the conversations around 'fully inclusive education systems'. This leads to the marginalisation of the Special Needs Education sector, a lack of resource mobilisation and unwillingness to discuss supporting the education of children with severe disabilities.

Local government, international donors and stakeholders are promoting the inclusive education agenda. They strive to create an inclusive learning environment in mainstream schools that would allow all children to learn, thrive and be safe. Although this intent is laudable and hopefully will lead to such fully inclusive schools, the current situation is very different.

World Education conducted research in 2022-2023 under the Girls' Education Challenge funded Strategic Approaches to Girls' Education (STAGE) project in Ghana. This GEC project successfully transitioned more than 17,000 formerly out-of-school girls into primary and secondary schools or, for older girls, into work. A tracer study confirmed that more than 90% of the girls are still in school two years after this transition and a similar proportion of older girls are successfully managing their income generation activities.

Around 1,000 girls involved in the project are living with a form of impairment, as indicated by data from a community mapping exercise using the Washington Group short set of questions. Facilitators and teachers were trained in inclusive pedagogical practices to support children with learning or physical impairments. Appropriate classroom arrangements and teaching and learning materials were created, and the girls were provided with assistive devices or referred to the Ghana Health Services for further assessment and support.

However, we did encounter a group of 19 girls with severe or profound disabilities, such as girls who are blind, deaf or face more severe intellectual disabilities. These girls were engaged during the Accelerated Learning Programme with parental and communal support. Nonetheless, the reality is that these girls cannot (yet) be accommodated in mainstream schools in many rural areas in Northern Ghana.

In the remote, poor communities in which we work, schools and teachers are not equipped to support children with such severe disabilities. Teachers are not trained, teaching and learning materials are unavailable and safeguarding standards are not in place to support their learning needs or provide appropriate care. We argue that we would be doing harm by placing these children in mainstream schools in their communities. After discussion with the Fund Manager and FCDO and in line with Ghana's inclusive education policy, children with severe disabilities were assessed by medical specialists. They were supported by the STAGE project to transition to Special Needs Education. In Ghana these schools are called 'Special Schools' and in the government sector are boarding schools. It is here that the challenge begins.

Preliminary findings from our research conducted in three schools in two regions highlight the specific challenges that children, parents/caregivers, and educators face in sending their children to these regional boarding schools.

One challenge is cost. On average it costs $500 per child per year, which allows them to travel accompanied by a trusted guide to special schools and return home during breaks. In addition, all students must bring their provisions for the year, such as clothing, products for personal hygiene, and supplemental food items. Unfortunately, none of the families we work with can commit to spending $500 annually.

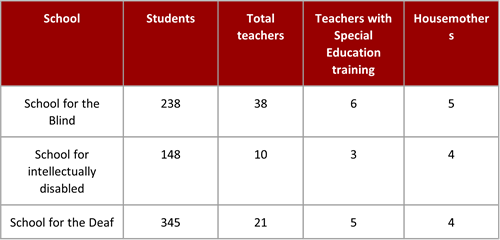

A second finding is that most teachers in the special schools we visited are not trained to teach children with severe disabilities. The table below illustrates the number of teachers who received special education training before being assigned to a special school. For example, during the research, we encountered teachers in a school for deaf students who were unable to sign effectively and teachers in a school for blind students who started working without being able to read Braille.

Housemothers are staff assigned to special schools to provide daily care and ensure the well-being of the children in school. They are on-campus day and night and work in shifts. However, the number of housemothers in each school we visited is insufficient, with housemothers responsible for between 35 to 80 children.

In addition, the curriculum is not specifically targeted towards children with various disabilities. All students are required to follow the same basic education curriculum. Teaching and learning materials provided to schools are regularly insufficient or inappropriate, and assistive technology is often unavailable. Class sizes are large, making it difficult for teachers to conduct individual education planning for each child.

“I have seen so many changes with Amelia. She is living independently now. She can even read and write.” Father of a STAGE girl who goes to the school for the blind

Many of these issues are partially fueled by a lack of awareness and prioritisation of Special Needs Education in Ghana and beyond. Less than 1% of the national education budget in Ghana goes to Special Needs Education, and international stakeholders and donors historically have not provided significant funds to support the government in improving Special Needs Education.

The preliminary findings of this research are clear. World Education has discussed these at the Comparative International Education Society conference in Washington DC on February 19, 2023.

It was a well-attended presentation with key personnel from Ghana's Ministry of Education, USAID Ghana attended. We consider this discussion a first step in awareness raising and aim to discuss it further with stakeholders in Ghana to validate the data and discuss challenges and potential solutions. Meanwhile, we want all stakeholders and international donors to rethink their investment priorities in inclusive education and focus on regular mainstream education and Special Needs Education in Ghana.

More discussion and research are needed. Therefore, World Education is looking to collaborate with other researchers, Disabled Persons Organisations, the Special Education Division and other stakeholders in Ghana to get a comprehensive picture of the state of Special Schools in Ghana.

“They have five senses. One of them might not be working but the other four are very, VERY active.” Headmistress talking about the capabilities of children with disabilities