Blog

Elevating the perspectives of marginalised adolescent girls: Exploring education journeys using the River of Life participatory approach

A recent study led by the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the University of Cambridge evaluated how Leave No Girl Behind (LNGB) projects, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office through the Girls’ Education Challenge, have affected the education and livelihood journeys of out-of-school marginalised adolescent girls.

The study paid particular attention to the extent to which the projects promoted the girls’ agency and life choices in these journeys. The research focused on three LNGB projects: Education for Life (EfL) in Kenya, Strategic Approaches to Girls’ Education (STAGE) in Ghana and Accelerating Life Skills Literacy and Numeracy of Out of School Adolescent Girls (Aarambha) in Nepal. This blog presents some of the stories from the adolescent girls, gathered using the River of Life visual story-telling approach. It then reflects on some lessons that could be relevant for others considering its use. All names used in the blog are pseudonyms to protect the identity of participants.

Using the River of Life participatory approach

LNGB projects focused on marginalised adolescent girls, including those who were married early, with children, with disabilities, and/or living in extreme poverty (among other characteristics depending on context). Our study aimed to explore the perspectives, choice, and agency of the adolescent girls to understand the extent to which LNGB projects met their needs. This required creating spaces where girls felt comfortable to express themselves. In doing so, it was important for the study to recognise and address the power dynamics that result in their marginalisation, and so contribute to making their perspectives invisible. This also involved being attentive to the fact that they might share sensitive information related to their vulnerabilities.

Therefore, the River of Life participatory approach was used to capture participants’ reflections on their life journeys using the metaphor of a river (see an example of the approach in action in Uganda here). Depending on the context, the river can also be drawn as a road or whatever is most relevant to the participants’ experiences. In one of the training sessions in Nepal, for example, there was discussion whether a mountain would be more appropriate.

Workshops took place in the community learning centres that the adolescent girls had attended as part of the LNGB projects. For adolescent girls aged under 18, parental or caregiver consent was sought for their participation. Workshops were organised according to whether girls had transitioned to formal schooling, skills-training, or work opportunities as part of the projects, or if they had dropped out of the LNGB project before completing the programme. There were approximately five adolescent girls per workshop, with a total of 98 participating across the three countries. Two facilitators and a psychosocial counsellor were present at each of the workshops.

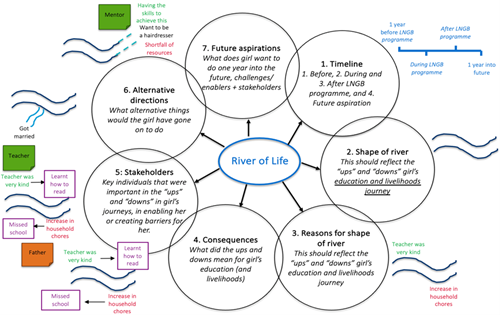

During the workshops, the adolescent girls used coloured pens, post-it notes and flip chart paper to draw their River of Life depicting their education and livelihood journeys (Figure 1). They identified challenges faced in schooling prior to joining the learning centre. These were represented by rocks, rapids and even crocodiles. They also included information on enablers, choices, and aspirations in relation to education and future livelihoods.

Figure 1: Steps to completing the River of Life drawing

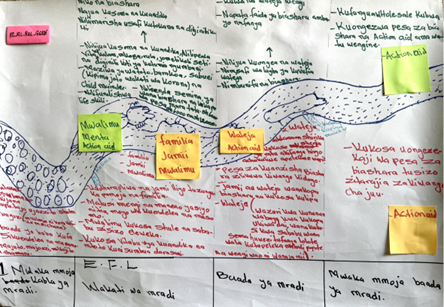

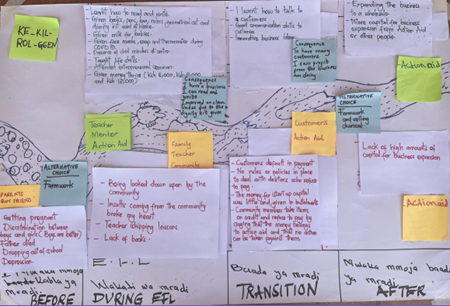

After the workshop, all the adolescent girls were interviewed individually, to explore issues raised in their own River of Life drawing. Following the interviews, the facilitators annotated the River of Life drawings to allow the data analysis team to interpret the information more easily e.g., translating what the adolescent girls had written into English, providing clarity on what the pictures meant, and any other information that was not immediately clear (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A pre- and post-annotated River of Life

Listening to adolescent girls’ stories through the River of Life

The River of Life drawings provided space for the adolescent girls to raise sensitive issues that they might have found more challenging to share during one-to-one interviews alone.

20-year-old Salemah from Kenya, for example, was a married adolescent girl with children. Her River of Life drawing documented the coercive and physical violence she was subjected to by her husband before, during and after joining the programme. Salemah identified how it helped her gain skills which gave her the confidence to be more independent from her husband, including being able to make her own decisions: “I still have problems but with the help I obtained, I have the thought of opening my business and being able to support myself and my children without depending on him anymore.”

15-year-old Noor from Nepal spoke of how she learnt to read and write the Nepali alphabet after taking part in the project. She wished to attend secondary school to achieve her aspirations of becoming a doctor. But Noor discussed how, after her time at the learning centre, her father forbade her from attending school now she was older and ready for marriage. She discussed the risks of physical violence she and her mother were vulnerable to should she attend school: “My father told me not to go [to school]. He thinks one should not go when they grow up. My mother doesn’t say anything on my behalf [as] then my father will beat my mother”.

For 20-year-old Ayaan from Kenya, her aspiration was to go to formal school to become a chemist. However, her age after completing her time at the learning centre meant she was unable to do this, as only younger adolescents aged 10 to 14 had this opportunity. Her second choice was to pursue an apprenticeship to become an electrician, but she said: “My husband refused me to do electrician because he said that is for men.” Instead, she focused on a business selling nuts, charcoal, and clothes.

Across all three of these stories, a common theme emerged, comparable to stories from other adolescent girls in the study: the projects helped to enhance their learning, confidence, and future education and livelihood opportunities. However, negative family and societal attitudes, which these projects alone cannot change, continued to persist, and remained a formidable barrier to adolescent girls’ education and livelihood aspirations.

Reflections on using the River of Life and lessons for the future

In using the River of Life approach, we identified some lessons from the challenges, alongside key benefits, that could be informative for others adopting a similar approach.

Challenges included:

• The workshops often over-ran due to the different speeds at which the adolescent girls completed their individual River of Life drawings. An important lesson was to allow for plenty of breaks and sufficient time between activities to avoid participant or researcher fatigue.

• One-to-one interviews with most adolescent girls took place the same day, following a lunch provided after the workshop. This was planned because of the distance some of the adolescent girls had to travel which meant that it was a long day. To address this, the team prioritised afternoon interviews for those who had furthest to travel, while other adolescent girls who lived close to the workshop venue returned for their interview the following day.

• Balancing the numbers of facilitators compared to the number of adolescent girls meant that a workshop setting was chosen to remove the power distance traditionally associated with one-to-one interviews, which is even more prevalent with marginalised populations. However, the study pilot revealed that some girls required more hands-on support than others. In each of the workshops, there were two facilitators (one to guide the workshop and one to support), a psychosocial counsellor, and a note-taker. Having more than one facilitator was crucial for those who required additional support, such as adolescent girls with babies, with visual impairments, or who had cognitive disabilities.

• Sharing the River of Life drawings is an important ethical consideration with participatory approaches such as the River of Life. In our study, the drawings were taken to the head offices of the respective data collection partners to enable them to annotate the drawings in a way that made them ready for analysis. We recognise, however that the adolescent girls may have wanted to keep a copy of their drawings, and this should be considered for future work of this kind.

Benefits included:

• The River of Life approach was an effective way to listen to adolescent girls’ voices as interviews with marginalised adolescent girls can often be fraught with the challenges caused by unequal power dynamics. By combining the River of Life with semi-structured one-to-one interviews, the adolescent girls were able to engage in conversations about potentially sensitive themes.

• The presence of a psychosocial counsellor helped to identify when the adolescent girls needed support by detecting signs of distress or trauma quickly and taking appropriate action. They offered the girls immediate support, as well as providing them with resources to seek further help from local networks.

• Using local knowledge and leadership networks such as local data collection partners was vital to the success of the workshops both during the training and data collection phases. These partners had worked with marginalised communities and experience using participatory approaches. As did local project implementers who had direct contact with participants and who could find replacements if needed. Lastly, engagement with community leaders (e.g., village chiefs and religious leaders) was important in facilitating access to suitable community spaces for the workshops.

• Participatory approaches allow for a relationship of trust to develop between researchers and participants. Facilitators also used a range of culturally appropriate icebreakers at the start of the workshops. These were important to help the adolescent girls – who were often very shy – to feel more at ease. The study also sequenced the data collection so that the workshop was held first, followed by the one-to-one interview. This meant that the adolescent girls were already familiar with those who interviewed them.

Using the River of Life approach (or indeed other participatory approaches) as part of a qualitative or mixed methods study can – as we found for our own study – help identify key themes upon which rich information can be further built upon. This is especially true when working with particularly vulnerable marginalised groups. The full study findings can be found here, while a report on the experience of using the River of Life approach can be found here.

This blog was first published on the IDS Participatory Methods blog website on 22 January 2024.